Over the past year, Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh have been grappling

with the challenge of finding durable housing for people displaced

during the 2020 war. The problem is not new for the Armenian

government: the country has been trying to resolve the housing

crisis for refugees displaced from Azerbaijan for over 30 years.

Using statistics, interviews, and other sources, Chai Khana explored

how government policy has shifted toward refugees over the

decades.

When Armenia declared its independence from the Soviet Union in

1991, it faced several immediate crises, including the ongoing war

with Azerbaijan and waves of refugees fleeing the fighting.

The most pressing was the war, which, according to the Armenian

government, displaced over a half a million ethnic Armenians,

360,000 of which moved to Armenia. Official Soviet census figures

put the number at closer to 352,000. Regardless of the exact amount,

the challenge was enormous for the struggling new state, especially

since the government was already facing hundreds of thousands of

displaced people due to the 1988 earthquake in the northern Armenian

town of Gyumri.

The last census of the USSR was done in 1989, which may not be a

reliable source to consider for this research, as the

Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict started prior to that. By 1988, both

populations were already mixing: Armenians fleeing Azerbaijan and

Azerbaijanis fleeing Armenia.

Several thousand ethnic Armenians (no official number available)

fled Azerbaijan and settled in Russia, USA and Europe. Many of them

never came to Armenia and went directly to third countries, but some

stayed in Armenia for some time before moving abroad to avoid the

economic crisis and ongoing war.

Aleksey Mnatsakanov was born in Baku and fled his hometown a week

before the Baku pogroms. “I was 12 so I remember everything very

well,” he says. Aleksey’s family first settled in Russia with some

relatives, but eventually moved to the USA.

Anahit Baghdasaryan’s parents were both born in Azerbaijan. Her

father moved to Armenia prior to the war; her mother was forced to

flee from Ganja in 1989.

“After the Sumgait events they realized they should move, that it

was dangerous to stay there,” Anahit says.

Emergency support for emerging crisis

In addition to the refugee crisis created by the war, the Armenian

government was also facing waves of ethnic Armenians seeking shelter

in the country from other post-Soviet conflicts, including in

Chechnya and neighboring Georgia. The U.S. Committee for Refugees

and Immigrants reported that 11,000 ethnic Armenians left their

homes in the former Soviet Union and resettled in Armenia. The

Armenian government, however, did not consider them refugees and

they were not eligible for the housing solutions created for those

who were displaced by the war with Azerbaijan.

A three-pronged housing policy

By 1999, five years after the end of the war, the government decided

to adopt a more organized approach to the housing crisis. In

November 1999 the Armenian government created the Department of

Regulation of Migration and Refugees to solve the refugee housing

issues and assist them to fully integrate into society.

The department created a program that aimed to house all eligible

refugees in 2000. It was unable to fully execute the program,

however, due to the lack of resources.

While the program fell short of its goal, by July 2004, 3800 refugee

families (approximately 15,000 people) had received housing,

including 300 who received assistance from the Armenian government.

The rest were housed through programs financed by international

donors, such as The Norwegian Refugee Council, The UN Refugee Agency

and the German Government.

“With the help of international donors, houses and cottages were

built in different regions,” Gagik Yeganyan, the former head of the

Migration Service of Armenia, says.

The district built in the city of Charentsavan over the course of

three stages (from 1995 to 2000) was financed by international

donors.

“According to international law, the hosting country does not have a

legal obligation to provide refugees with shelter and

accommodation,” Yeganyan says. “But this was a question that had

other layers to it: people became refugees as a result of an

Armenian movement, the Karabakh Movement, and because of the

conflict and the war everyone paid some price.”

He notes that the population in Armenia paid the price of living in

economic hardship; the population of Karabakh paid the price of

constant bombing; and the Armenian diaspora paid by helping Armenia

economically and, in some cases, even coming and fighting. The

Armenian population of Soviet Azerbaijan paid one of the biggest

prices: losing their houses and fortunes and being subjected to

violence and forcefully displaced.

“It was a moral question already, and that is how we presented it to

the government. It does not matter that the person came to his/her

“motherland.” They had lost everything, and the poverty could make

them leave Armenia,” Yeganyan says, adding that in 2004 the

committee went to all dormitories and hotels housing refugees to

collect data on the population and their living conditions.

In May 2004, ten years after the end of the war, the Armenian

government sought to resolve the problem through the act “On the

Priority Housing Program for Persons Deported from Azerbaijan in

1988-1992.” The act outlined a new, $16-million-dollar program to

address the housing issue, as well as the department’s efforts to

date. It underscored the financial issue, noting that fully solving

the problem would cost more than $50 million.

Based on the numbers outlined in the act, approximately 65,000

people displaced from Azerbaijan remained in the country and needed

housing. These numbers are not enough to calculate how many total

refugees from Azerbaijan remained in the country, however. An

unknown number were able to settle with relatives or friends. Some

were even able to exchange apartments and houses in Azerbaijan with

Azerbaijanis who were forced to leave Armenia.

The act of 2004 noted that 10,000 refugee families (approximately

40,000 people) still needed housing, including 3470 families

(approximately 13,880 people) living in extreme poverty. The new

government program created by the act envisioned resolving the

housing problem through housing vouchers, government-built cottages,

and giving refugees the chance to privatize the government-owned

buildings where they were living (dormitories, old hotel rooms,

etc).

“Starting from 2005 a

huge amount of money was allocated from the budget every year to

solve this issue. Approximately 1200 families received apartment

purchase vouchers by 2008; each year vouchers were given to 300-400

families,” Yeganyan says, adding that approximately 200 of those

families did not manage to obtain houses, as the vouchers had to be

used within six months of being issued.

“After 2008, due to the global financial crisis, Armenia had to

abandon many social programs, including this one,” Yeganyan says.

Three decades of displacement

“They completely

stopped talking about refugees after 2009,” Oksana Musayelyan, a

refugee from Baku and the founder of Refugee Voice NGO, says.

“The problem became normalized as people had been living here for

more than 15 years and many of them did not have refugee status

anymore. Some of them had to take citizenship.I don’t want to say

they were “forced,” but that was the feeling,” Oksanna says.

“The refugee status was the only thing that gave them some guarantee

that their rights are recognized by someone in the international

community. Taking citizenship would mean to give up on the chance to

get a certificate as a refugee or receive restitution one day. But

at the same time the status limited people a lot.”

Oksanna says even borrowing a book from a library was an issue for

those with refugee status. “There were no social programs to

integrate refugees into society, which requires an integration

policy in the county and we didn’t have one. They were saying: ‘you

are an Armenian, you came to Armenia, and so what’s the problem?’”

Oksanna says, noting that this was one of the reasons for the

massive migration of the refugees from Armenia to other

countries.

“Armenia was not

able to use the potential that Armenian refugees from Azerbaijan

brought with them,” she says.

Oksanna started to advocate for housing for refugees in 2017. With

her organization, Refugee Voice, she collected data from

approximately 20,000 people who had not gotten Armenian citizenship

yet and still had refugee status.

Oksanna received her housing voucher in 2015, although not through

the three-stage program. A mental health institute opened in the

building where she was living at the time, and the government

allocated housing vouchers to the nine families (five of which were

refugee families) living in the building.

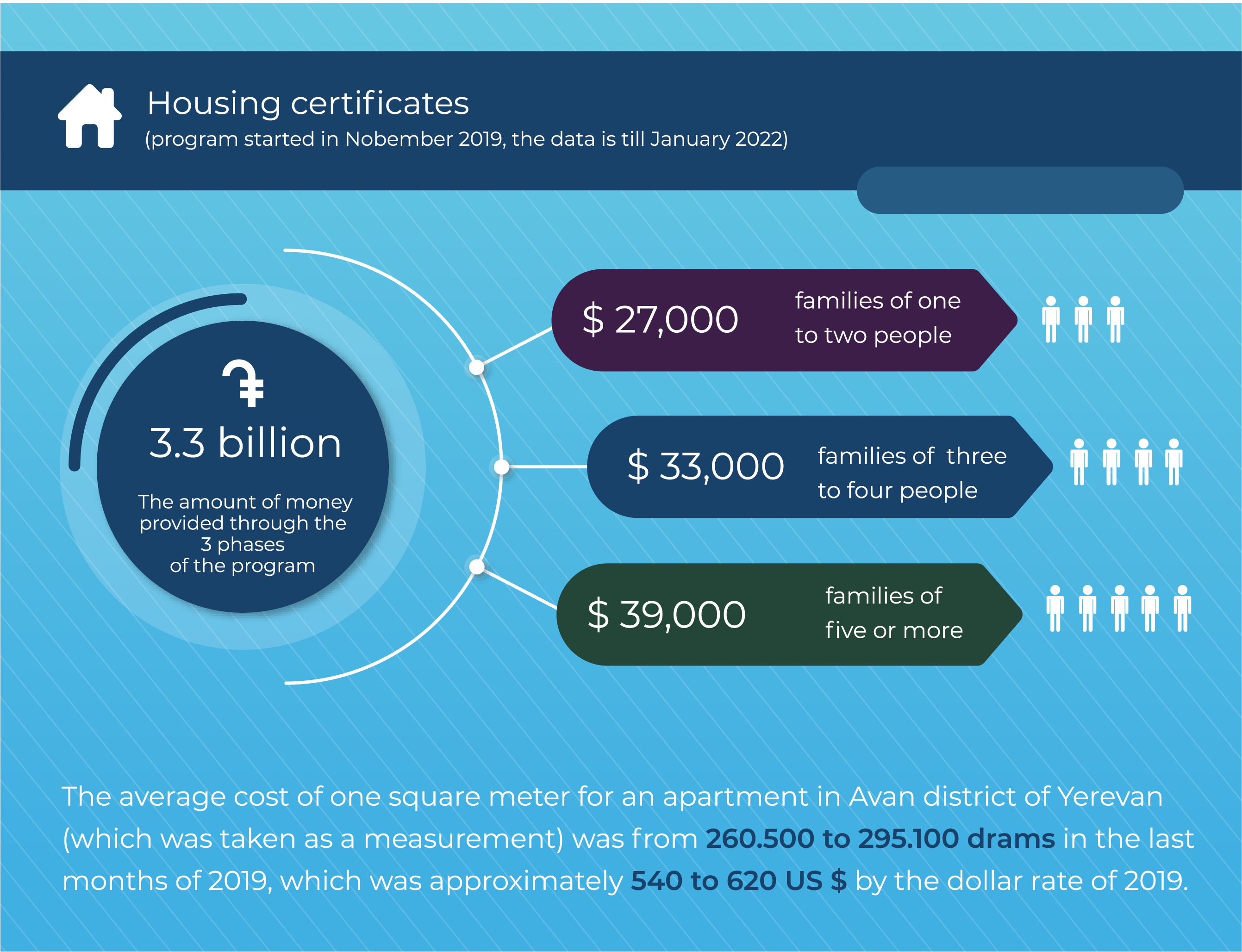

The housing program was forgotten until 2019, when the newly elected

government decided to allocate budgetary funds to address the

issue.

“Between 2008 to 2019

many families who lived in extremely bad conditions left Armenia,”

Nelly Davtyan, the Public Relations Coordinator of Migration Service

of Armenia, says.

Under the 2019 program, socially vulnerable families living in

Yerevan received housing vouchers.

Rima Abrahamyan and her family had to flee Baku in 1988. For a while they rented an apartment but eventually settled in an old university building in Yerevan where several families had already relocated. Abrahamyan’s family received a housing voucher under the 2019 program. Abrahamyan bought her house and moved to the city of Armavir in January 2021.

According to the Department of Regulation of Migration and Refugees, this program will resolve the housing crisis for the most vulnerable in Yerevan. Once it is complete, a new three-stage program will start for the 250 refugee families living in extreme poverty in the regions.